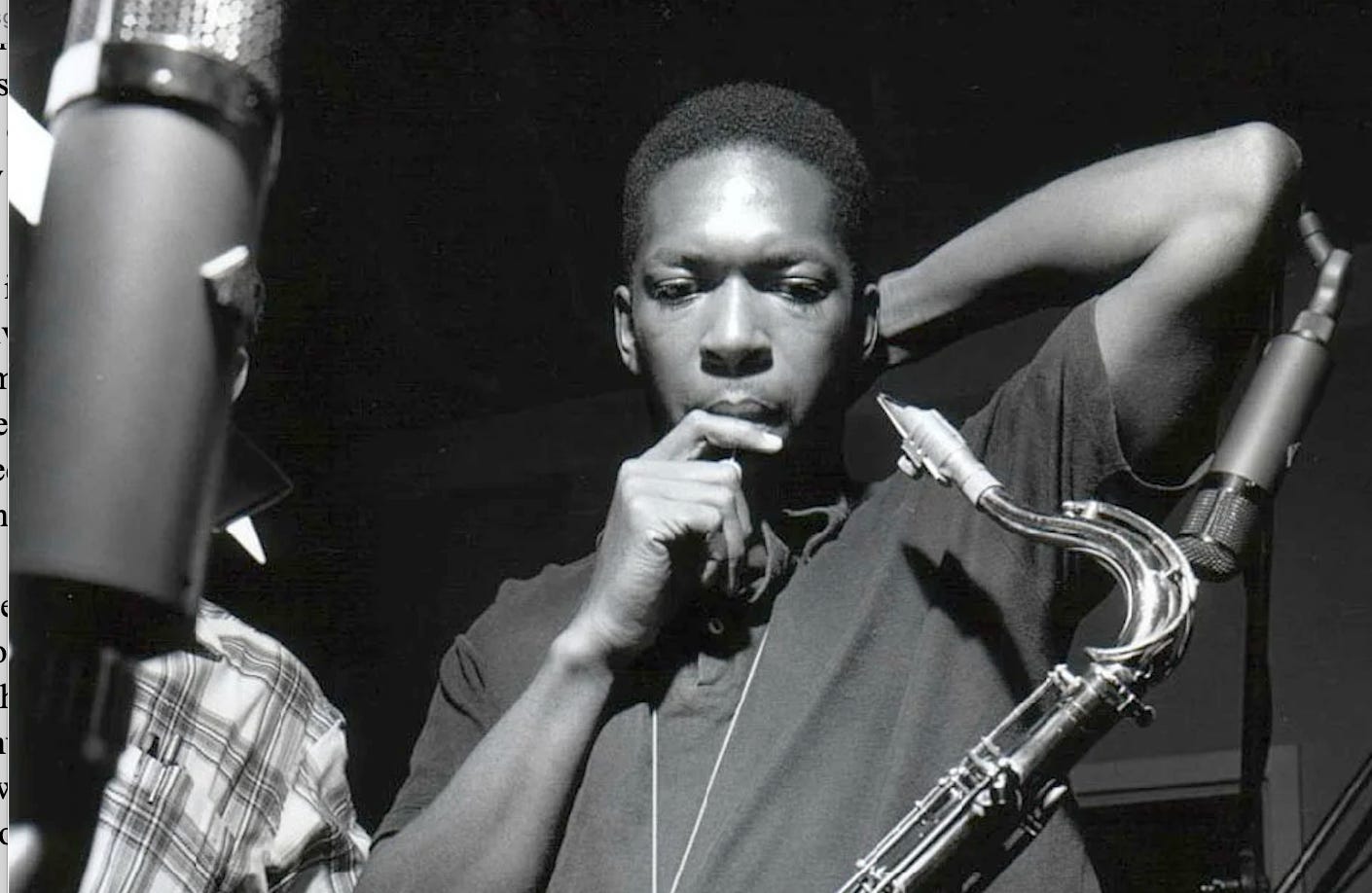

For most of the 1950s, tenor saxophonist John Coltrane recorded straight-ahead jazz for Prestige and Blue Note. In 1958, he began playing modal jazz with the Miles Davis Sextet on Milestones (1958) and continued with his own Giant Steps (1959), Davis’s Kind of Blue (1959), My Favorite Things (1961) and other albums for Atlantic and Impulse. Modal jazz uses specific scales for improvisation rather than chord progressions, allowing musicians to improvise for longer periods. [Photo above of John Coltrane by Francis Wolff ©Mosaic Images]

From 1965 to 1967, the year of his death, Coltrane explored free jazz, beginning with his album Ascension. The ferocity and intensity of his playing not only was hypnotic but had a huge influence on rock and fusion artists who sought to play extended solos. His later albums featured this style of playing for entire sides of an album.

Bret Primack, who for years was known as the Jazz Video Guy, conducting on-camera interviews with jazz musicians and uploading them to YouTube, has just written a memoir, How John Coltrane Changed Me: A Jazz Journey. In the book, he writes about how Coltrane’s later period inspired him and still does. You can buy it as a Kindle for just $6.95 (go here). [Photo above of Bret Primack in Mexico by Sherrie Posternak]

Last week, I caught up with Bret to talk about his love for Coltrane and why the saxophonist’s music had such an impact on his life and his new book:

JazzWax: Where did you grow up and what did your parents do for work?

Bret Primack: I grew up in West Hartford, Ct., about 100 miles from New York, in suburbia. My dad began as a professional musician. During World War II, he was a pianist stationed in London and led a big band called the Skyliners that backed Bob Hope on USO tours. After he was discharged and returned home, he continued to play weekend gigs and weddings, but he abandoned playing full-time for more steady work. He held a series of office jobs where he worked as an accountant at various companies, but he was never happy with that. Once he gave up music, he resented it and never played the piano we had at home. My mother was a homemaker who looked after me and my two younger brothers, Terry and Ross.

JW: Did your father take his resentment out on the family?

BP: Not at all. He was a very quiet guy. My mom was an A-type neurotic who laid all of her stuff on us. She had tremendous anger and frustration. During the war, she was a WAVE— the U.S. Naval Reserve’s women’s branch set up in 1942 to have women fill non-combat roles in the States. She was based in New York. After the war, she went from being a purposeful working woman to a housewife responsible for raising the family. Dad went to work and came home, and she was unhappy with that life. So her anger and frustration came out on a regular basis, almost as a form of torture for us. Both of my parents also regularly worried out loud about money. A lot of therapy helped me.

JW: Did a lack of money squeeze your home life?

BP: Not really. We didn’t take lavish vacations or belong to a country club but we had everything we needed. Our house was nice and there were two cars. My dad worked his day job. On the weekends he played gigs, but he barely kept his hand in music.

JW: Was that a bad thing or a good thing?

BP: The unfortunate big thing for me was he never encouraged me to practice the trumpet. He said, “I don’t want you going into the music business.” He was emphatic about that. If he had given me some encouragement, I might have become a musician. But I can’t complain. My life has been incredible.

JW: How did your passion for music start, and how were you first exposed to jazz?

BP: When I was 6, I saw Louis Armstrong on The Ed Sullivan Show. His joy and playing pulled me in.

JW: Where did you go to college and what did you study?

BP: As high-school graduation neared, I applied to NYU’s film school, at their Tisch School of the Arts. I didn’t get in, so I spent a year at Hofstra University. During my freshman year, I met director Francis Ford Coppola. He had gone to Hofstra and encouraged me to read the classics and get into theater, which I did at Hofstra. But Manhattan had a magical lure. I couldn’t wait to move there. I transferred to Tisch in 1968 and was there for three years.

JW: Wait—how did you meet Coppola?

BP: I went to a film symposium in Hartford where Coppola spoke. After, I sent him a letter and he wrote back. He was very encouraging. In 1967, he was on Long Island shooting a film called The Rain People. I arranged to have breakfast with him at a local hotel, and he invited me to spend the morning with him. He introduced me to filmmaker George Lucas. Right then and there, I should have volunteered to be an intern on the set for free, but my parents would have gone nuts if I left college. I didn’t have enough self-confidence to make that move. I often wonder what my life would have been like had I done so.

JW: How was film school at NYU?

BP: Great. Director Marty Scorsese was one of my teachers and very encouraging. His love of movies, his knowledge and his willingness to share it were huge motivators. After college, I needed direction and became fascinated by technology. I bought an early Apple computer in 1984 and helped build out Jazz Central Station, the first online jazz site, in the 1990s.

JW: What was Jazz Central Station?

BP: It was the brainchild of Larry Rosen, who had done well with GRP Records as the first jazz label to release CDs and produce smooth jazz in 1979. He had seen an article I wrote in Jazz Times magazine. Jazz Central Station featured jazz sound clips, interviews and photos. It was too early yet for video. The site also sold things and was geared to jazz musicians.

JW: What happened?

BP: Amazon picked up speed in 1998 as people began to shop online, and Jazz Central Station’s revenue dried up. So I went to work for another dot-com company called Global Music Network. It featured audio and video music online. It went belly-up in 2001 with the dot-com crash. By 2004, camcorders and computer-editing software had become more affordable and easier to use. I invested in gear. YouTube launched in 2005 and I began uploading jazz video interviews and became known as the Jazz Video Guy.

JW: When did you start listening regularly to jazz?

BP: When I was 12, I began listening to jazz on FM radio. The music spoke to me immediately. The first recording we had in our house when my parents bought a hi-fi was Duke Ellington’s Nutcracker Suite. Duke Ellington had visited and performed at my high school.

JW: When did you first hear John Coltrane?

BP: I knew about him as a reader of Downbeat magazine in the 1960s, but I didn’t hear his music until 1970, when I first heard A Love Supreme. That album was a big deal for me. I had heard Kind of Blue, but it didn’t move me. Coltrane’s 1960s recordings did. The sound of his tenor and soprano saxophones, with their almost human voice, affected me deeply.

JW: Some have argued that his music in the 1960s was an expression meant for black listeners during a period of political and social turmoil. As a white listener who began listening to Coltrane after his death, what was it that caught you?

BP: Coltrane’s 1960s work was rooted in the black experience. Alabama was his reaction to the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing in Birmingham, Ala., in September 1963. A Love Supreme grew from a spiritual awakening. I don’t claim to fully grasp those dimensions. As a white listener in the 1970s, I connected to something universal: the sound of pushing past limits, refusing to abide by boundaries. Ascension and his late work with drummer Rashied Ali showed me someone dismantling conventions. Over time, I’ve come to grasp the cultural context more fully, which makes the music even more powerful. What stays with me is Coltrane’s relentless search, his proof that transformation is always possible—born from black struggle yet resonating far beyond it. It was different and healing.

JW: What did you need healing from?

BP: Making some sense out of this life. It came to me at a time when I was trying to figure out who I was at age 20. There had been no spirituality or religion in my life, so jazz held my life together. Coltrane inspired me. I studied his music and found that what made him unique was the way he kept changing and searching for meaning. I was doing the same. Many musicians wanted to succeed by doing the same things over and over. Coltrane was looking for something new.

JW: How did Coltrane’s 1960s recordings change you?

BP: They helped me be more open about all possibilities. Even though I get to a point where I’ve found a solution, I keep going. In other words, life is a continuous search, a continuous struggle that never ends. With Coltrane in my life, I evolved from film student to web guy to documentarian to a guy who posted jazz videos to a blogger now living in Mexico. If you look at what Coltrane did from 1957 to 1967, his transition is extraordinary. Nothing like that had ever been done before in music. I’ve always been a risk-taker, and Coltrane’s search for an answer has been very motivating.

JW: Is there a connection between Coltrane and your relocation in 2022 to the Central Highlands in Mexico?

BP: Not really, That was a decision made for us by Sherrie, my wife and artist. When I initially told people I was going to move to Mexico, they couldn’t believe it. Many said, “Why take a chance like that? You’re living in Tucson, Ariz., in a nice house.”

JW: What was your reply?

BP: If Coltrane taught me anything, you have to keep moving forward, and forward was Mexico. Here, people treat each other differently. They take care of each other. There’s a compassion and a strong spiritualism here. There’s also a sense of colorful joy that didn’t exist for me in the U.S. Coltrane taught me to integrate spirituality into my life, and that’s what I did.

JW: Is this something you knew in advance or discovered after the move?

BP: I didn’t realize how important spiritualism was to me until we moved. There’s a history here in Mexico. There’s a culture. Unfortunately, most Americans do not know much about Mexico. The media paints a very negative picture. It’s a completely different place than has been characterized.

JW: Is there a connection between listening to Coltrane and who you’ve become now?

BP: Absolutely. And Coltrane was portable. He’s here with me now.

JW: Do you find that when you listen to Coltrane, in Mexico, is there a different message and feeling?

BP: I have a much stronger connection to nature here, because of where I live and our house and our garden. Coltrane’s music has a lot of dimensions. There’s a more lyrical, tender aspect of it that I experience now than in the past. If I’m in my garden, when I put on Coltrane’s Crescent, Dear Lord or Naima, the music feels like an extension of the nature I see around me.

JW: Have you taken to Coltrane on your headset during a hike into the mountains?

BP: I don’t need to. I know the music well, so it’s in my head. But I think of it often. For example, there’s an ancient site of Mesoamerican pyramids called Teotihuacan, about 40 minutes northeast of Mexico City. It’s unbelievable when you see these things. How did people build them? What were they like? Coltrane’s later music, such as Meditations and Transition, elevated what I saw when I thought about the music. I could hear that civilization evolving while they were building the pyramids.

JW: What was the motivation to write your book?

BP: To give readers a sense of how John Coltrane’s spiritual music fit into my life and helped motivate me to continuously seek a higher purpose and the meaning of the world around me.

JW: For readers unfamiliar with Coltrane’s 1960s recordings who want to ease into it, what five tracks would you recommend, in order?

BP: My choices would be…

Equinox, from Coltrane’s Sound

Lush Life, from John Coltrane with Johnny Hartman

In a Sentimental Mood, from Duke Ellington and John Coltrane

Wise One, from Crescent

And Dear Lord, from Transition

Great final question and answer Marc and Bret!

That's a great conversation with Bret! I'm a subscriber of his YouTube-Channel "Jazz Video Guy" since years but I didn't know that you in such a good contact with Bret. And he helped you with "Substack" 🙂. I just found out that his book is also available as paperback. So, I will think about it tonight if I will buy it as Kindle or good old paperback.