Interview: Bruce Weber on Chet Baker

A new double album is due with previously unreleased music by the trumpeter-singer for the 1988 documentary 'Let's Get Lost'

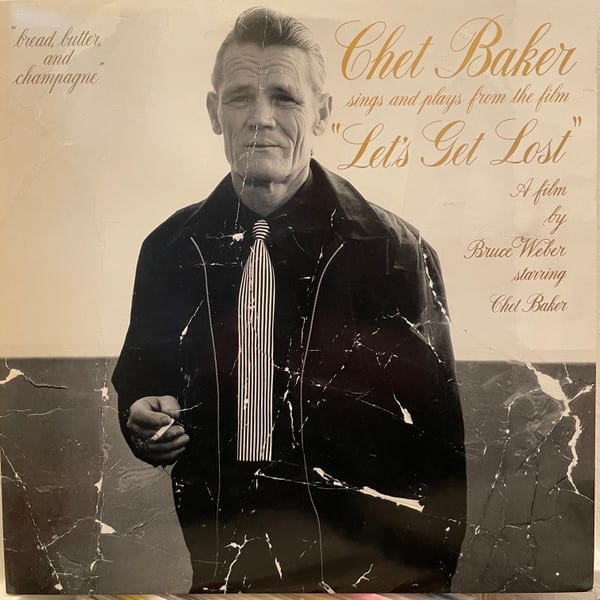

Chet Baker never saw Let’s Get Lost—Bruce Weber’s film on the trumpeter-singer’s life and one of the finest jazz documentaries ever made. Baker died in May 1988, four months before the film’s release. [Photo above of Chet Baker in 1988 courtesy of Bruce Weber]

Now, Bruce, his wife, Nan Bush, and bassist John Leftwich are in the process of assembling a sequel. It’s being culled from previously unreleased footage and music recorded at the time and will be called Swimming by Moonlight: New Music From the Documentary Let’s Get Lost. There’s no official release date yet. It’s still in production.

What we do have coming is Chet Baker Performs & Sings: Swimming by Moonlight, a two-LP/two-CD soundtrack album to be released by Slow Down Sounds. The two-CD set will be out Nov. 7 and the double vinyl on Nov. 14.

It turns out that when the original Let’s Get Lost was re-issued two years ago in 4K, director Bruce Weber needed several new songs because some of the licenses for the film’s songs had expired.

Back then, Bruce, Nan and John dipped into the Baker material to find substitutes. That’s when they discovered they had upward of 60 previously unreleased tracks plus film of Baker recording some of them in the studio. That’s when they realized they had more than enough material for a new film. They chose 16 songs for a new soundtrack, and the music was ready first.

Last week, I Zoom-interviewed Bruce Weber (above) and bassist John Leftwich on Baker, the new album and the forthcoming movie, and why pianist Russ Freeman wasn’t in the original film:

JazzWax: Bruce, why do you think Chet Baker’s late period in the 1980s is so dreamy and heavily romantic?

Bruce Weber: Chet was older in the 1980s, but he was still a kid inside—curious and exploring. He also really liked to take his time with a song then. I’m a big Peggy Lee fan, and I remember watching her at a session when she was quite ill. She was singing, and lyricist Sammy Cahn was there, who I really admire. Peggy was singing Sammy and Jimmy Van Heusen’s The Second Time Around. She was singing so slowly that Sammy thought her memory was slipping and yelled out the lyrics to her. She looked up and smiled and said, “Sammy, I know the song. I just really like to take my time.” Chet was deep like that with everything.

JW: Deep?

BW: As a person. He loved living, despite his demons. Remember, this guy’s favorite sport was deep-sea diving. In 1988, Nan Bush, my wife and agent, would go to these film festivals where Let’s Get Lost was entered, and people would come up to us after and say, “Oh, I can’t believe we weren’t in the film.”

One couple said, “Chet was our babysitter for six months.” Just the idea that somebody hired him as a babysitter when he was an adult and that he wanted to do it was fantastic. I mean, how many grownups would do this? Chet was always an adult child. Even dogs pick up on it.

JW: How so?

BW: I have a lot of dogs and they can sense adolescence. There’s a story that was told to me that when Chet arrived in Germany on tour with a friend, they were carrying a lot of drugs. He went through customs and wound up where German shepherd dogs sniffed around everything. Chet sat on the floor and played with the dog. Then Chet and the friend walked out with all their stuff.

JW: What other ways?

BW: If you said no to him, he’d get really angry. He couldn’t handle it, just like a little kid. One time in Paris, we were walking to dinner. He said, “I need you to rent me a car. I want to drive from Paris to Rome to pick up my bass player and come back.” I said, “Chet, I can’t do that for you.” He said, “Man, why not? What’s wrong?” I said, “Because you’re a terrible driver.”

He said, “Is that because you believe all the stories about me?” I said, “No, because I’ve been with you in a car. You’re a lousy driver and I know it.” He said, “Yeah, but I want to go there.” And I said, “Well, the answer is no.” I sound like my father talking to me.

JW: Did that ruin dinner?

BW: Not at all. At the restaurant, he had a drink and they were playing music. He was singing along with the song. You wouldn’t have thought he had a care in the world or that he was just told he wasn’t going to get his way with the car. Another time, I said, “Hey, Chet, I was just in New York and friends introduced me to Gerry Mulligan. I was really excited, and at dinner I asked him if he’d like to be in the film. Gerry said, yes.” Chet said, “Oh, he doesn’t know anything about me.” Which was so puzzling.

When we started to film, Chet was singing Imagination. I’ll never forget it. We we’re in the recording studio and just before we started rolling film, I’m thinking, “Oh my God, I’m just starting out to make films. Not only am I making a film, but we’re making a record.” It was like double-trouble, right? These guys were purists. The guy who recorded it, Jim Mooney, asked me, “What jazz people do you like?” I said, “Well, I grew up on Ella Fitzgerald.” He stopped me and said. “No, there’s only one singer—Billie Holiday, and then it stops right there.” They all knew their stuff.

JW: When Baker starts singing Imagination, what happened?

BW; We could barely hear him. A great bunch of Los Angeles studio guys were backing him—Frank Strazzeri on piano, John Leftwich on bass and Steve Backer on drums. As he sang, the mic was literally almost in his mouth. He loved old mics, to get an older sound, but he was so close to it. After the take, all these musicians and others were back in the booth talking when the playback started. Then we had the moment of decision. It’s almost like in bullfighting.

JW: What happened?

BW: Tape rolls and I had to ask them to be quiet a couple times so we could hear. It goes quiet and all of a sudden every person in that room had their mouth open. They were hearing a song that they have probably heard a million times, and Chet’s close-mike take took the song to a whole new level.

JW: When you first approached Chet to do the documentary, what was his reaction?

BW: We were in New York. He was happy, even though he had no idea who I was or what I’d done. And he never talked to me about paying him money to do it. Money wasn’t motivating for him on something like this, thank God. All he wanted was for me to take some photographs of him with his girlfriend, Diane Vavra. I was really so excited and said, “Hey, yeah, I’ll do that, but can we come uptown and see you at your place? I know you’re staying at your bass player’s apartment up in Harlem” He said, “Yeah, that’d be really nice.”

JW: What happened next?

BW: We get there and we were like these total nerds coming to this jazzy bare-bones apartment where the neon light outside shined on and off in the window. Chet was in bed in the bedroom with this little trumpet—it looked like a toy, almost.

JW: He really new nothing of your reputation?

BW: God, no, of course not. No, no. I could have been anybody off the street. I said, “I want to shoot you singing Blame It on My Youth,” this Oscar Levant- Edward Heyman song. Chet said, “Yeah, yeah.” I said, “We’re going to California.” He said, “I’m going out to San Jose to visit my girlfriend.” I said, “Well, why don’t we get together. You can come down to L.A. and we’ll do it.” After the experience with the bed, I realized what I had for the film.

JW: What exactly did you have?

BW: A person with enormous charisma who was a natural character. He was so magical up in that apartment that he just turned the place into an apartment in Tahiti. There was such an aura of fantasy around him.

JW: Was he confident you knew what you were doing or would even get it done?

BW: I don’t think he truly cared and didn’t believe in us until we did that Imagination taping. In the booth, all the guys were poking fun at him and my team and me, as musicians do. A lot of verbal towel-snapping. When I finally told them to be quiet, Chet liked that. I was suddenly someone who was protecting him, like a bodyguard. Bassist John Leftwich was so gentle and patient with Chet to get him to do what we needed.

JW: What was the noticeable difference in Baker?

BW: After that, Chet immediately wanted to please me, Nan and John. I don’t think he ever looked at the filming as anything bigger than that. Hanging out with someone who was passionate about him and willing to protect him.

JW: How was the recording handled? Was it done after the documentary’s filming or before?

John Leftwich (above): At the same time, intermingled.

JW: What did you notice about Baker throughout the recording sessions?

JL: Probably his repose. He’d just be there witnessing everything with an expression that said, “Maybe I’ll sing, maybe I won’t.” So it’s a sense that he’s almost reflecting all the time and just being himself, but when he wanted to record, boom, you had to catch it quick because he didn’t like a second take. He liked just one. But we’d all encourage him to do a second.

BW: You see this in Let’s Get Lost. There’s a moment where he’s ready to go and says, “Are we ready, Frank, or did you want to rehearse the intro again?” You can see it’s a different Chet—the worker Chet, impatient Chet, master artist Chet.

JW: John?

JL: Right. I don’t even think he viewed it as work. He was just ready and wanted to go. If he wanted to go out for dinner, if he wanted to talk to his girlfriend, if he wanted to sing and play a tune—he sees that moment as his only shot, like a child. He was in that moment of desire, suddenly determined and not happy if everyone isn’t on board. Chet wasn’t playing three-dimensional chess. He was just going on an inward feeling and an instinct with the understanding that the moment was essential.

JW: Basically, you’ve just outlined a very long definition of cool.

JL: [Laught] Yeah, I guess you could say that.

JW: Bruce?

BW: Well, when you asked John this question about being cool, it reminded me of something I had said to Chet. With most people you’re working with, you might make idle conversation, like, “So how are you today?” or “Wow, what a beautiful day out there today.” Something simple to break the ice. Chet’s answer would be, “Yeah, nice day for a kite.” Every time I see a kite now, I think about that line.

JW: I assume you were into the Chet Baker mystique, his music and his vulnerability before you even approached him. Did working with Baker and experiencing his quirks shatter your romantic impression of him?

BW: No, those quirks only fortified my feelings. We had the money and the time to do the film the way I wanted, and I was working with three other people who were infatuated with his music and the essence of him as a human being, as a man. These people were Nan, John and Jeff Price, our cameraman. I never expected to get the same kind of support and enthusiasm from Chet.

JW: Why not?

BW: We were really kind of square for him. I think he loved that. Most people would have been getting high with him and doing stuff like that, and then never would be able to find him the next day. We were working so hard we weren’t even drinking much. We were too wiped out at the end of a day, emotionally. Like John said, you didn’t know if he was going to show up, and if he did, whether he was going to sing. It was always a drama.

JW: When you say he had respect for the squareness of you guys, do you think what he was really respecting was your integrity and work ethic?

BW: Yeah, exactly. I think he just loved it when he went to a recording studio. Sometimes he’d work with pianist Frank Strazzeri and get really uptight about the piano’s sound. But he loved Frank and they worked together and knew each other. And John was so protective of him. If there was an issue, John would gently say, “Oh, Chet, let’s do it this way or that way.”

JW: What was the most confounding thing about Baker?

JL: You’d expect him to do a take and he wouldn’t want to. Or he wouldn’t show up—as in Bruce’s short, Looking for Chet, Again, In All The Familiar Places. That really explains it. Nan was one of the keys to this whole thing. She and Chet had a kind of mystical connection. She could even sense where he was that day, and would be right. Chet wanted Nan to manage him because she really got him. Chet seemed to have feminine feelings that women responded to.

JW: Where do you think that came from?

BW: When we went to Oklahoma to film his family, I thought I was going to see this beautiful farm or a ranch or something out of a Norman Rockwell painting. I envisioned his mom and his wife would be there along with his kids and it would be a wholesome, Midwest scene.

I get there, and they all lived in a little apartment. They had no food in the refrigerator. And I was like, “Oh my God, I can’t believe this.” But they were in their place. I didn’t see it until Jeff was filming, way over in the corner.

JW: See what?

BW: Way over in the corner was this big bust of Chet. We got to know a record producer who loved Chet’s music so much, he left his wife and kids to move into an L.A. apartment with him. He sold his piano, all his sound equipment, everything to support him. One day Chet came home and said, “Hey man, I need some money.” The guy said, “I’m wiped out. I just have two cans of Chef Boyardee spaghetti in the kitchen.”

JW: What did Chet do?

BW: Chet said, “Man, I’m out of here.” As for that bust in the corner, it was owned by the guy. Chet’s daughter took it, I guess, when she was helping Chet get his stuff out.

JW: Tell me about the new album and forthcoming film project?

JL: After the Let’s Get Lost film was reissued two years ago with a 4K restoration, we had to swap out some of the clips because our music licenses had expired. So we re-edited to get the new music in and swapped out videos for others we had in the can. That’s when Bruce and Nan realized they had all these sessions that were recorded and some of them filmed. So they had another 50 or 60 songs. From the tapes, we pulled 16 for the new album—Swimming by Moonlight: New Music From the Documentary Let’s Get Lost.

JW: That’s an enormous amount of additional material. Are you also using tape of Baker singing from the sessions?

JL: Yes. Bruce is pulling them together and adding interviews. It will be like a sequel to Let’s Get Lost, except the focus will be on the music.

JW: On the new album, the personnel is much broader than the original soundtrack. Was music overdubbed?

JL: Yes. In some cases, Bruce wanted some of the songs to be more gentle or different for the upcoming film. He also wanted Chet’s voice more up front. Or in some cases, the piano was played a little harsh, so Bruce wanted a guitar in there or different instrumentation. The album is a soundtrack and needed to feel bigger. And there was some editing. The tape was 40 years old, so we did our best to sort that out.

JW: Bruce?

BW: We have a series of music videos of the songs on Swimming by Moonlight. We may have 10 videos on this new film. We’re bringing them together so they flow like one film held together with interviews.

JW: John did you have the same level of passion for Baker as Bruce?

JL: Yeah, I bought his albums when I was a kid and I learned the songs. The solos from his She Was Too Good For Me album in 1975 on CTI are just fantastic. I transcribed some of his solos and learned to sing a few of the songs. I always loved him.

JW: What did Chet think of your “Zingaro” solo, which is a classic?

JL: Not much. Most of the feelings we had for what we were doing were expressed without words. When we were working on an arrangement, we’d say, “OK, Frank, you take this first part. John, you’re the second. Should we try an intro?” So it was really the common way that jazz musicians work is they come up with something real quick.

JW: What’s your favorite song on the new album?

BW: I Can Dream, Can’t I? I just love it. In this world we live in now, to be able to hear those lyrics and give some kind of hope for things, you can’t beat it.

JW: John?

JL: Quiet Nights, because of the way he sings it. The way he interprets the song is so fresh, and you really feel the sentiment and vulnerability. Then he takes a great trumpet solo. Hubert Laws added a great flute solo after, and they interplayed at the end. But there’s a bunch of great songs. I love Make Me Rainbows and I’ll Be Around.

JW: John, did you get a sense that Baker seemed mystified by his own beauty? I don’t mean physical beauty. The fact that he could play and sing so beautifully. Beauty is what he was all about in many respects.

JL: I don’t think he thought about it. I think his expression was all in the moment. He didn’t really view himself in the third person. He was just in the moment being himself and feeling out what was special about a song and how he wanted to project that. In that sense, he was really just there, being himself.

JW: As we know, we’re talking about a person with two personalities. There’s the jerk who borrowed money and didn’t pay it back. Then there’s this guy who could be so incredibly beautiful when playing and singing—really get inside a song. Was music just a way for the bad guy to pay the bills? Or was he a beautiful cat trapped inside desperation?

BW: What you just said reminds of that line from My Foolish Heart—”There’s a line between love and fascination.” Chet was kind of fascinating. How did he get away with so much and still have a lot of soul?

JW: Yes, how did he pull that off?

BW: I think he really knew how to seduce people. It wasn’t a con. It was a pure expression of his heart. I think he needed to do it. That was the real drug he was on. It wasn’t all the other stuff. He needed to be seductive. If he walked into a room, he would want everybody to be fascinated by him, to be interested. There’s something interesting about why people like that need it so badly.

JW: What’s the answer?

BW: I don’t know. It’s strange. He’s strange, and that’s interesting. You never know what he was going to do next. For a photographer and a filmmaker, that was really challenging and great for me. I was very lucky. It was a gift that I was given to capture all of it.

JW: Ever get a sense of why he became hooked on drugs?

JL: There’s a strong correlation between a mood that you set when you’re playing something and a story that you’re trying to tell musically. The feeling of a drug suspends self-judgment and you just experience it. And when you’re in that moment of creativity, it’s the same thing. You’re suspending judgment and not judging yourself. You’re saying, “Oh, I should play this higher or louder.” You’re just in the moment.

JW: How do drugs enter that though?

JL: With drugs, it would seem, it’s that same suspension of self-judgment and becoming part of a story and just kind of flowing with it. I think it’s the same.

JW: Bruce?

BW: I think the pressure to create something unique is just extraordinarily compared to most other things. It’s like climbing Mount Everest without oxygen. I remember that when we interviewed Chet’s mom, she said to me, “I used to say to Chet, why can’t you play and be like Dave Brubeck? He’s a really clean-cut guy. He’s got some sons, kids, he’s got a home, a wife.” After she said that, I thought, given all that Chet has accomplished and winning all these awards and everything, it still wasn’t good enough for his mother.

The jazz musician has a different pressure than other musicians, requiring a high level of sensitivity. As a result, I think even the weather affects them. You know what I mean? Their translation of sadness is so deep and they just have to be supported all the time.

JW: What are you most proud of in the upcoming film?

JL: Bruce and Nan were able to set up an environment for Chet so that he could show himself completely. It wasn’t just another studio date or another documentary. Chet was able to show himself more fully. And I think he enjoyed it.

JW: Bruce?

BW: He wanted this film to be a little bit of history about him for posterity. When you have somebody like that, if you’re a photographer and you’re photographing somebody, you want that interesting element. I remember photographing Nelson Mandela. He talked a little bit about his life, but not so much. When I looked in his eyes, he absolutely had no anger or nothing like it. He just wanted to be admired. I think that’s a normal thing for exceptional people.

JW: Is assembling the new movie part of this feeling?

BW: It is. I’m so glad we have him back in our lives again on tape. That’s what’s been so great. And I’ve been really excited. I think about it at night. I think about it when I get up in the morning. I just totally live it.

JW: Do you wish you could give him a call and let him see some of the stuff that you’re doing?

BW: Of course. He never saw anything we did. I don’t even know if he ever heard anything that he did except for a playback in the studio. He died in May 1988. The film had its premiere at the 1988 Toronto Film Festival, four months later.

JW: Why is Chet Baker still important?

JL: As artists, our job is to tell a story that people can experience and get something from emotionally without having to go through that experience themselves. That’s when an artist is a pioneer. As a member of a documentary team, you’re going out there with the subject, you’re feeling things, you’re experiencing life and then you’re telling a story on film so people have a chance to experience those things, too. That’s what Chet was doing on-camera and in the studio. He was summing up a lot of his emotions and telling his own story in a more true way than albums and concerts ever could.

JW: Bruce? But let me frame the question a little differently: when people hear Chet Baker for the first time, the music pulls them in. They respond. But why? What are they responding to?

BW: Chet had a lot of grace as a musician. That’s the thing that I was really attracted to—his grace. As a filmmaker, I just hope we got some of that for audiences in the new film because in the end, even though he shook people down and was messed up all the time, he gave somebody something back.

JW: One last question: Why didn’t you use Russ Freeman on piano for the film? Freeman recorded all of those great tracks with him back in the early 1950s.

BW: We tried, but we couldn’t get in touch with Russ. He was nowhere to be found, probably away on a gig where he planned to stay for a while. We were thrilled to work with Frank Strazzeri—he had the perfect temperament for Chet. Russ would have wanted to do a lot more takes, and Chet wouldn’t have been able to deal with that.

To buy Swimming by Moonlight: New Music From the Documentary Let’s Get Lost, go here.

Here’s Chet Baker singing and playing I Can Dream Can’t I?, from the forthcoming Swimming by Moonlight, with John Leftwich on bass and Ricardo Silveira on guitar…

And here’s Relaxin’, with Chet Baker on trumpet, Frank Strazzeri on piano, John Leftwich on bass and Ralph Penland on drums…

Can't wait (well actually, I can as I'll have to) for Swimming to come out. For what little it's worth, I was watching Monk videos last night & it struck me how similar his way of improvising was to that of Art Tatum's, of all people - given a ballad, they both just refigured the melody, rather than improvising on the chords… also you can best understand what Monk is hearing as he plays by watching his dancing feet.

Excellent interview and looks to be a great follow up to ‘Let’s Get Lost’